Reporting Highlights

- Community Divisions: A tribal lending business in Minto, Alaska, is bringing in much-needed revenue but also dividing the community over ethical concerns and questions about who benefits.

- Legal Issues: Two suits allege Minto’s partners receive the bulk of the lending revenue. Among those named: Jay McGraw — son of Dr. Phil — who is linked to a firm assisting the tribe.

- Unhappy Borrowers: Minto’s lending operations have been the subject of numerous consumer complaints, with borrowers frustrated by interest rates far higher than most states allow.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Dr. Phil, the powerhouse TV personality, has long dispensed practical advice to anyone hoping to avoid financial ruin — advice he’s shared with his millions of viewers. “No. 1 is avoid debt like the plague,” he’s said.

On other episodes of his syndicated talk show, he’s urged people to pay off their costliest obligations first: “You got to get rid of that high-interest debt.”

Yet for thousands of people mired in debt, Dr. Phil’s eldest son has been part of the problem, an investigation by ProPublica and the Anchorage Daily News found.

Jay McGraw, a TV producer, became involved in the payday lending industry over a decade ago and has been affiliated with a range of financial services businesses, more recently launching a firm that sells used cars online at costly interest rates and targets Texans with low or no credit.

Earlier this year, McGraw settled a federal civil suit that had accused him of playing a key role in CreditServe Inc., a financial technology consulting firm that helps arrange small-dollar consumer loans online — with interest rates that can exceed 700% — via a company owned by a Native American tribe in Alaska.

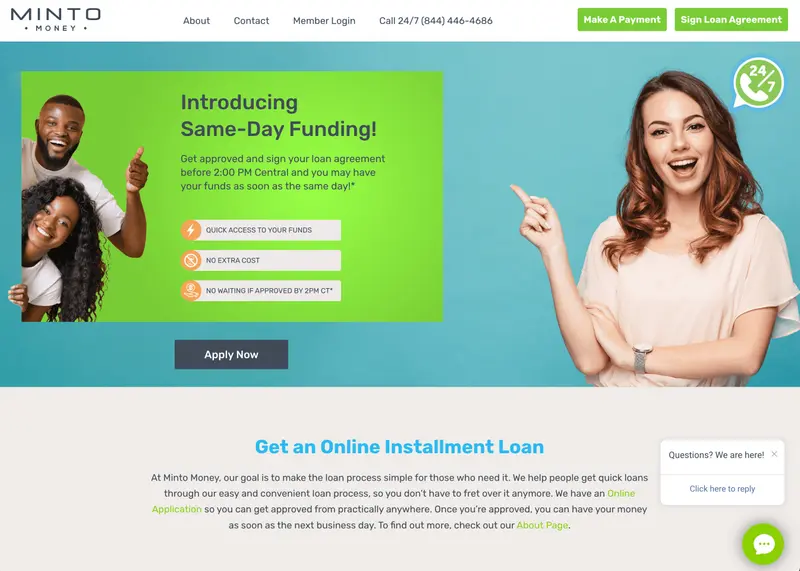

The tribal lending operation, Minto Money, is based in the log cabin village of Minto, 50 miles northwest of Fairbanks, and has delivered a new revenue stream to the community since its inception in 2018. But it’s also created a rift within the tribe, as some members are appalled by the burdens inflicted on poor and desperate people.

“It’s bringing in a lot of money. But it’s off the misery of the people on the other end who are taking out these loans,” said Darrell Frank, a former chief of the tribe. “That’s not right. That’s not what the elders set this tribal council up for.”

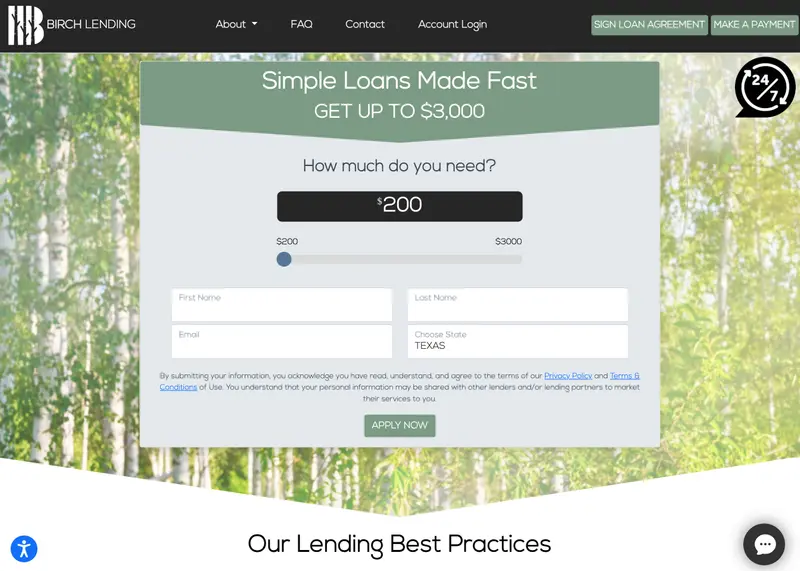

There’s documented harm. As of July 2024, the Federal Trade Commission had received more than 280 consumer complaints about Minto’s lending operations. That total includes complaints forwarded from the Better Business Bureau, where Minto Money holds an “F” rating. Customers who took out loans — which range from $200 to $3,000 — pleaded for relief from onerous terms that allowed Minto Money to claw back the sums multiple times over through automatic bank withdrawals.

Credit:

Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic

“This loan is outrageous with interest over 700%!” one person complained to the Better Business Bureau about having paid $4,167 on a $1,200 loan from Minto Money. “I am one step away from filing from bankruptcy.”

A federal suit filed in Illinois in November by five Minto Money borrowers contends that McGraw has provided “tens of millions of dollars” in capital for the loans. CreditServe provides the infrastructure to market, underwrite and collect on them while “the Tribe is merely a front” and shares in only a small percentage of the revenue, according to the suit.

It called McGraw the “enterprise’s principal beneficiary,” asserting that he and CreditServe’s CEO, Eric Welch, have collected “hundreds of millions of dollars of payments made by consumers.”

The suit alleged that McGraw and the other defendants, including Minto Money, violated state usury laws and federal prohibitions against collecting unlawful debt. A confidential settlement resolved the lawsuit in early May but left open the possibility that other Minto Money customers could file similar suits in the future.

A. Paul Heeringa, who is representing McGraw, Welch and CreditServe, wrote in an email to reporters that “our clients cannot comment on any of your questions, or the case generally, other than to say that the allegations in the Complaint are not facts and were not proven to be true, and that our clients categorically deny the allegations.”

CreditServe was set up by a Hollywood lawyer who has represented the McGraws, California records show. Its principal address in the Larchmont Village neighborhood of Los Angeles is a box in a mail shop that also has served as the published address for many other McGraw family companies.

There is nothing in the public record linking Dr. Phil — whose full name is Phil McGraw — to the lending businesses, including CreditServe.

A lawyer for Phil McGraw said McGraw declined to comment for this story but shared a short statement from a spokesperson for Merit Street Media, which airs “Dr. Phil Primetime.”

“Dr. Phil knows his son Jay to be a smart, strong, caring human being and while he does not know his business Dr. Phil supports him 100%,” the statement said. “The suggestion that Jay’s business ignores or is even comparable or relevant to advice from Dr. Phil or Dr. Phil Primetime on Merit Street Media is false and only included in your article as click bait.”

Lori Baker, chief of the Minto tribal government, said in an email that the Minto Village Council had no comment in response to questions about the lending operations and members’ concerns.

Among critics of Minto’s lending operation, the idea that outsiders can’t be trusted is central to their opposition.

One Minto elder who no longer lives in the community worries that strangers are taking advantage of the tribe and its loan customers alike. The elder asked not to be named because of concerns about reprisals for criticizing the lucrative business.

“They are exploiting our village,” the elder said. “It is not right taking from poor people to get yourself rich.”

Credit:

Marc Lester/Anchorage Daily News

Distant Partners

Jay McGraw got into the lending business as he branched out from other ventures. Minto got into it to help the people of the village.

By the time the company that would become CreditServe was formed in 2011, McGraw had obtained a law degree, gone into the film production business with his father, pioneered a highly successful daily syndicated medical advice show called “The Doctors” and written a series of self-help books for teens.

More quietly, he ventured into the high-interest lending business. Corporation papers in 2013 listed McGraw as the president of Helping Hand Financial Inc., a company that offered payday loans online at CashCash.com. “Get the CashCash You Need Fast!” the firm’s website exhorted.

The following year, when CreditServe Inc. filed an amendment to its articles of incorporation with the California secretary of state, it showed McGraw as president and secretary. Helping Hand Financial dissolved in 2017, but CreditServe remained in business. In both ventures, McGraw teamed up with Welch.

McGraw is not currently listed in California records as a top officer at CreditServe. But the federal suit in Illinois describes his role as significant. “McGraw and Welch dominate CreditServe and are responsible for all key decisions made by it,” the complaint states.

Welch declined to comment for this story.

He and McGraw are also named on corporation papers for Cherry Auto Finance Inc., formed in 2021, which offers easy financing for used cars online at cherrycars.com, appealing to subprime borrowers. The site posts estimated annual percentage rates of 22.4%.

Just as desperate borrowers turn to unconventional and high-interest loans, a few dozen Native American tribes in dire need of economic rescue have been drawn to the business side of that same industry.

The community of 160 in Minto faces the same challenges as many Native villages in Alaska, which are set in hard-to-reach places on ancestral hunting and fishing lands. Village leaders have struggled to build an economy in a remote place with few jobs, spotty internet and sky-high costs.

In 2018, Doug Isaacson, a non-tribal member working for Minto’s economic development arm, brought Minto an idea that could help the village. Isaacson — the former mayor of North Pole, a city outside Fairbanks that revels in its association with Christmas — suggested that the tribe get involved in the lending business. Tribes in America are in demand as business partners because they can claim that, as sovereign entities, their operations are exempt from state interest rate caps. Critics of such lending partnerships have called them “rent-a-tribe.”

To the tribal council, the lending business sounded like a way to create jobs and bring in much-needed revenue. The household income in Minto is about 30% lower than the statewide median. But groceries are more expensive and gas costs $7 a gallon.

Minto adopted a Tribal Credit Code, stating that “E-commerce represents a new ray of economic hope for the Tribe and its members.”

The Illinois lawsuit contends that on paper, the tribe appears to control the lending operation, but CreditServe provides the key services, including “lead generation, technology platforms, payment processing, and collection procedures.” Most of the money also flows to CreditServe, which has an office in suburban Austin, Texas, according to the suit.

McGraw’s lifestyle stands in sharp contrast to those living in Minto. He owns a lakeside mansion in the Austin area, valued at over $6 million. A real estate listing noted that the gated home features a “glass ceiling, life-size fireplaces, 2nd floor tower and an 85 foot infinity pool & spa overlooking miles of unobstructed views,” with “guest house, elevator tram and boat dock.”

The Instagram pages for McGraw and his wife, a former Playboy model, portray a life of affluence, with photos of excursions to Paris, Napa Valley, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Cabo San Lucas and Palm Beach. There are golf outings and time on a yacht.

In Minto, people live in single-story log homes. They enjoy trapping wolves and beavers, hunting geese and watching school basketball games. Many worry about protecting the land and wildlife.

“Used to see a lot of moose by the village; right now just two,” minutes of a 2020 Minto fish and game advisory committee meeting state. “Global changes have really affected us.”

Credit:

Marc Lester/Anchorage Daily News

Money and Controversy

There are no outward signs in the village of a massive online lending operation. The headquarters listed on the Minto Money business license is the address of the tribe’s two-story lodge, which houses the tribal council offices, a nutrition program for elders, a community gathering space, and rooms rented to tourists and hunters.

The business license is signed by Shane Thin Elk, listed as commissioner of Minto’s financial regulatory body, tasked with oversight of the lending businesses. Thin Elk is a member of a different tribe and doesn’t live in Alaska. Reached by phone, he hung up on a reporter.

The tribe started with a single lending website — Minto Money — and later launched another, Birch Lending. Neither company lends to people in Alaska.

Once it got underway, the lending business took off. The Illinois lawsuit contends that “McGraw, CreditServe, and Welch have collected more than $500 million dollars from consumers” over the last four years.

Minto’s take was small in comparison. Still, it has made a difference.

ProPublica and the Anchorage Daily News obtained documents for Minto Money showing dramatic growth, from $2 million in annual revenue in 2020 to nearly $7 million in 2022. A former tribal lending manager for the operation, Cameron Winfrey, said that in 2024 that figure reached $12 million for all its lending operations.

Credit:

Obtained by ProPublica

Online lending “has thus far surpassed all expectations and provided enormous benefits to our community,” Winfrey wrote to the Minto Village Council in a January 2024 letter.

In an accompanying report, he listed some of the benefits that the lending business generated. He noted that $1.8 million was distributed to the Village Council in 2023, up about 50% from the prior year. Money went to the Minto library and computer lab as well as community organizations.

Winfrey also wrote that $627,000 was paid out in salaries and benefits in 2023 for employees of the tribe’s economic development corporation, known as BEDCO, and its subsidiaries, which includes Minto Money. He told ProPublica and the Anchorage Daily News that only a few people in Minto work for the lending operation.

Notably, the profit enabled the tribe to do what most tribes cannot: help fix its local school.

Yukon-Koyukuk School District Superintendent Kerry Boyd said the Minto tribe’s economic development corporation offered a surprise windfall when district officials discovered rising material and construction costs for a new gymnasium had increased the price tag by millions of dollars.

The tribe paid more than $3.2 million to finish the new gym, she said. A 2024 letter from BEDCO to the Minto tribal council stated that the money donated to the gym came from lending revenue.

In her more than 16 years running the district, Boyd had never seen such a generous donation. “I said, ‘Wow, this is almost unheard of.”

Credit:

Marc Lester/Anchorage Daily News

Many residents can’t say for sure where the lending money is going but point to newfound largesse. Folks get their heating fuel tanks filled by the tribal government. Some members receive “hardship” grants. There was money for a youth center. Musical instruments for the worship center. Dogsled races. A holiday party.

Still, some tribal members wonder why more money isn’t spread around. A handful of residents are calling for audits, greater transparency and federal investigations.

Some people thought the lending business would seed other economic development and lead to regular dividend checks. Instead, there is infighting and bitterness about who in the tribe receives the money. The division pits year-round Minto residents against members who live outside the village, in Fairbanks or elsewhere.

“If you don’t live in Minto, you don’t get shit,” said lending opponent Frank, the former chief. He is seeking an audit and a halt to the enterprise.

Once a tribe starts taking in large sums, it’s rare for internal disputes to go public.

“It’s a blessing and a curse,” one tribal member said recently. “We’re blessed that we get all this money, and it’s a curse because with money comes greed.”

“And some people don’t know the difference.”

Credit:

Marc Lester/Anchorage Daily News

Unhappy Customers and Legal Threats

Isaacson, the non-tribal Alaskan who promoted the idea, has shrugged off concerns about legal problems.

In a 2023 email obtained by reporters, Isaacson wrote, “Lawsuits are the cost of doing business these days.” He noted that “in no century have money lenders ever been revered, but they have always been essential.” (Isaacson told reporters he no longer works on tribal lending operations and could not comment.)

The Minto tribe’s business entities have been sued in federal court by consumers at least 17 times. The tribe has argued that arbitration agreements signed by borrowers, as well as tribal sovereign immunity, protect the businesses from lawsuits. In at least one suit, it expressly denied the characterization of Minto Money as a “rent-a-tribe” operation.

Several federal cases have been dismissed on sovereign immunity grounds, but more often they have settled quickly without reaching the discovery phase that could reveal more details about the lending operation’s structure.

It’s unlikely that the legal risks will end with the private settlement in the Illinois case. Ten days after that settlement, the plaintiffs’ lawyers filed a new federal suit on behalf of three different borrowers, making the same allegations against McGraw, Welch, Minto Money and CreditServe. The latest suit adds a debt collection agency as a defendant.

Across the country, other tribal lending operations have been subject to large settlements in recent years, including a tribe in Wisconsin that also is alleged in federal lawsuits to have partnered with CreditServe, among other outside entities. That tribe, the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, settled a federal class-action lawsuit in Virginia last year for $1.4 billion in loan forgiveness and $37 million in payments to customers and lawyers on the case. Of that, $2 million came from tribal council members named in the suit, while the rest came from business partners. (CreditServe was not named in the Virginia case or settlement.)

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which already had a spotty record of overseeing high-interest lending, is being gutted by the Trump administration. But a handful of states have pushed back against tribal lenders. In December, in response to complaints, the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions issued a warning advising consumers that Minto Money and Birch Lending are not registered to conduct business in the state. And in late April, the Massachusetts Division of Banks publicly advised borrowers to avoid predatory loans “including from tribal lenders,” listing Minto Money and Birch Lending as examples.

Minto Money already avoids lending in 10 states, primarily where attorneys have acted forcefully to protect consumers, though Massachusetts and Washington are not among the states it shuns.

In recent months, the tribal council consolidated its control over the lending business, removing Winfrey from both his position as Minto Money’s general manager and his seat on the council after a bitter dispute. Tribal leaders criticized his performance.

But Winfrey, who said Minto Money ranked among the country’s top-earning tribal lending businesses during his tenure, believed he was ousted because he had started asking too many questions about where the money was going.

He had planned to pitch the idea of tribal lending to other Alaska villages.

“They need the money,” he said one afternoon in February. But by May, he had met with only one community. Leaders there were wary of the idea, and Winfrey said that he, too, had started having second thoughts.

“They said, ‘Isn’t this a rent-a-tribe thing?’ I flat out said, ‘Yes. That’s exactly what it is.’ ”

The “tribe gets pennies,” he told an Anchorage Daily News reporter. “It should be the other way around, where the tribe gets all the funds and CreditServe gets crumbs.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.

]