Some years ago, I dismiss a publication of forgettable social networks that refers to the “three co-ado branches” or the government. A friend, an intelligent journalist immersed in American political history, replied with a soft correction reminding me that Congress was the “supreme branch”, agreeing its State I of article I in the Constitution of the United States.

It turns out that we were both wrong, although for slightly different reasons.

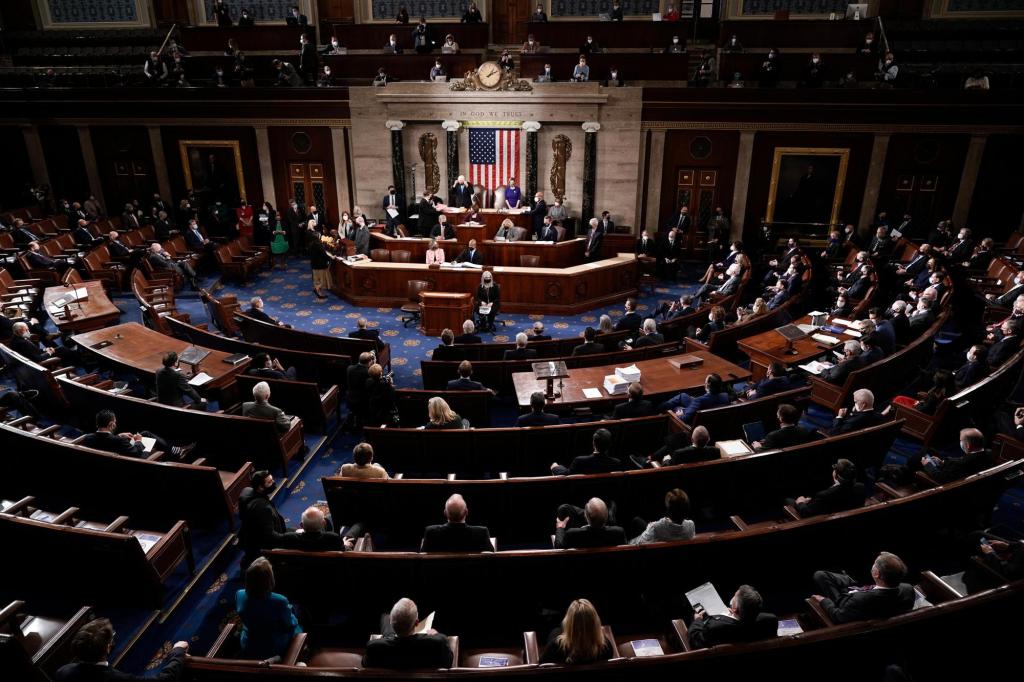

Since the change of the century, Congress has worked more and more like a quasi-parliament rather than as an independent branch of the Government, the legislative branch, to be precise. Instead of jealously protecting the different powers they grant them under the Constitution, members of the House of Representatives and the Senate, both Democrats and Republicans, voluntarily, almost Gleefy, yield the authority of the exception.

This phenomenon is prior to the second mandate of President Donald Trump and the main current republican majorities and fulfilled in Capitol Hill, Althegh, to be clear, it certainly extends to both (more about that at one time). Are there exceptions? Sure. But on this matter, the exceptions demonstrate the rule, explained Yuval Levin, director of Social, Cultural and Constitutional Studies of the American Enterprise Institute, a group of conservative experts in Washington, DC

“The president’s party in Congress only works as the president’s party in Congress, instead of the separate legislative branch,” Levin said in a telephone interview. “The opposition party functions as the party of the anti-president in Congress, and do not really work with each other in a way that is separated from the president’s agenda.”

In other words, the only time legislators disagree with a president who violates their constitutional prerogatives, if not the usurpes directly, when they are the other parts that make the infringing and usurpes. It is not very “supreme.” Nor is it very “equal equal.” Perhaps “the subordinate branch” is a better way to describe Congress. (The Judicial Branch – Article III – is, like the presidents, not shy to exercise constitutional power).

‘Party separation’

That the legislative branch ended here is part of a product of the movements of the Democrats of Congress that are carried out from the 1970 White often and others or Syty of Syty of White offelysial and others, or they, give off with reading and they, give off with reading and they – Stripual Stripual and them – Stripual Stripual and them. His muscle and concentrate political power in the hands of party leaders. In the House of Representatives, this resulted in the consolidation of power with the president and in the Senate, with the leader of the majority. Range legislators were effectively castrated. Ironically, this was done to frustrate the Executive Power.

“The Congress ended, because it was centralized, becoming a player in our presidential policy,” said Levin. Representatives and senators are understood, above all, as critics or supporters of the president.

Levin continued: “The separation of the parties has overcome the separation of powers.”

With Trump stretching the limits of the Executive Authority, there is a renewed approach in which selfless in the exercise of the members of the power of Congress seem to be.

President 45 and 47 is occupied by reducing or dismantling the government agencies created by the Congress Statute. And Yes, Trump is Threatening to Ignore The “Power of the Purse” Law of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House of the House From the house of the house of the house or of the house or of the house, buried in its storm of executive orders, there are even more captures of power at the expense of the congress.

But Trump is not the first president to overcome the limits of his prerogatives of article II, nor the Republicans of the Congress today are unique in his preparation to accept.

Democrat Joe Biden did it; Remember your unconstitutional program of student-bucle forgiveness. Democrat Barack Obama did it; Remember your decision of “pen and telephone” to grant permanent residence to certain illegal immigrants. Republican George W. Bush did it; Remember the signature statements that declare that it would not apply aspects of the legislation that opposed. And not once the Democrats (in the case of Biden and Obama) or the Republicans (in the case of Bush) did anything about it. In fact, they encouraged them to a large extent, as is the case in some cases until now, a little more than two months after Trump’s second presidency.

Warning signals

Another manifestation of this trend: Congress regularly has problems accepting government expenses and generally approves legislation that leaves the details to bureaucrats and rules creators in the executive branch agencies, which allows the elephant respectives to the violent reaction event of the voters.

Another signal: the number of vetoes in the White House has collapsed over the years. Before this recent trend of formation of the Congress, Republican President Ronald Reagan issued 78 vetoes in his eight years in office. As the trend gathered strongly, the Democratic president, Bill Clinton, vetoed 37 bills in his two terms. But the presidents of two periods Bush and Obama vetoed each one 12. There was a slight problem or veto for the duration of Trump their first term (10) and by Biden (13), but nothing that would approach the era of Reagan.

“In a parliamentary system, the Executive comes and is part of the legislative branch, without separation of powers and small controls and balances. It is an essential rule of the party,” says Jeff Brauer, a Keachstone College Political Farivo.

It is not likely that the continuous abdication of power of Congress will end soon.

Brauer points out that “probable voters do not understand the complexities or differences that distinguish the American system from parliamentary systems, and perhaps they don’t care.” Like their representatives and senators, they want a setback from Congress against the presidents to those who oppose. But they seem to prefer the presentation in the case of the presidents they support. In fact, it is this preference that discourages the Democrats and Republicans to tell a president of his own “no” party when it gets over.

Possible, an extended period or a divided government could change things. Possible, even the disappointment in Congress, which apparently exists, Tom Reynolds, a former republican member of the Buffalo House of Representatives, New York, told me. “I talk to the members all the time and I see frustration,” he said. However, the challenge to ensure that the legislative branch claims its power, as Brauer pointed out, is that legislators are reacting to the perceived will of voters.

That is something that Reynolds, who retired from Congress in 2009 and now works in government relations, understands well. It was his party campaign manager, as president of the National Committee of the Republican Congress in the electoral cycles of 2004 and 2006. “What has been added to this (problem of a subordinate legislative branch) is a very polarized base of both parties.”

David M. Drucker is the Bloomberg columnist. © 2025 Bloomberg. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency.

]