Hidden between the three -hour lines for sampling sales, the luxury boutiques that sell $ 4,000 bags and street vendors selling $ 100 of those bags, in Soho, is a time portal.

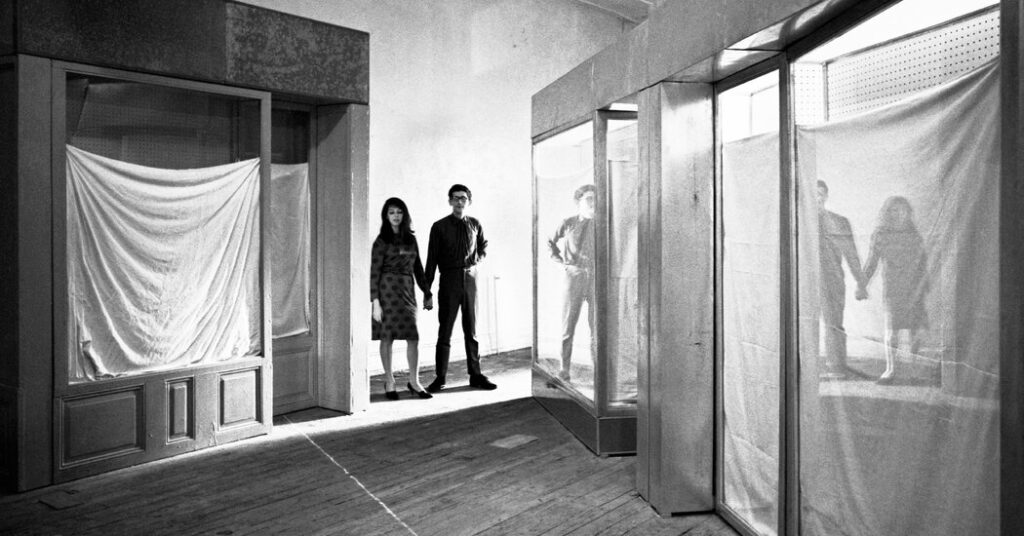

The five-story building in 48 Howard Street is where, for approximately 50 years, the conceptual artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude lived and worked. Much has changed in the neighborhood since the 1960s, when the couple moved for the first time there, renting two floors for only $ 150 per month. The value of the property has increased: the average rental of a property in Soho these days is $ 7,750, according to Zumper, but inside, the house remains almost exactly as it was when they occupied it. The study of the upper floor still has sketches of Christo, art supplies perfectly arranged in cookie cans and a bottle of unopened coca-cool (his son, Cyril, loved Coca-Cola). Below, where they ate and slept, the baratijas and the family photos surround the table of the dining room and the stools that he built to provide the space.

Shortly after Christo and Jeanne-Claude were in the neighborhood, in 1971, Soho was prayed to allow certain artists to live and work in their industrial lofts, even more solidifying their Bohemia condition. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Barbara Kruger, in Kawara and Richard Prince had lived in Soho. Now, more than five decades later, many of the artists of that time have died or abandoned the neighborhood, and the question of what to do with their studies arises.

Jeanne-Claude died in 2009, and in 2020, Christ did so. Since then, 48 Howard’s Future has been uncertain. Its base uses the building as its office, but the walls deteriorate, the paint is peeling and the facade has needed renewal. The possibility of opening the home to the public is being explored, but that could mean having to make structural updates to take it to the code and make it accessible, a possible expensive task that is not of its authenticity.

“I consider the apartment and the study as part of our own file, especially because Christo and Jeanne-Claude built the place with their own hands, designed it, and he literally built everything, from the walls to the Giovitor, said Lorenza’s manager.” We want to find a way to keep their legacy alive, preserving the space where they live and worked. “

Christo and Jeanne-Claude were known for their mass and specific facilities of the site that explored themes of Efemerías and Public Space. They never accepted the money from the sponsors, fined their own projects, regardless of the scale, to remain independent and avoid commercial influence. In 1995, they wrapped the Reichstag, the German Parliament building, in 100,000 square meters of fabric. A decade later in New York, the couple installed 7,503 “doors” of saffron in Central Park.

They created fleeting and monumental pieces that were engineering and negotiation feats. Its facilities of intense debates involved with governments and were with protests from environmentalists. The resulting works were owned by anyone, but they could be experimental of all, changing the way the public interacted with art completely. “Our work is a cry of freedom,” Christo often said in interviews.

Earlier this year, coinciding with the twentieth anniversary of the doors, the shed had a retrospective that highlights the unrealized projects of the couple, in Central Park, the public could see an augmented reality version of the work. It is not surprising that his works still resonate in the New York after today’s Covid, where many aspects of the city’s life are largely unaffordable and public space feels increasingly threatened, the search for the son of equality and emotion.

At a time when the creation of art on such a scale feels impossible without a corporate sponsor, when most visual acrobatics are shallow advertising tires, Christo’s preservation and Jeanne-Claude’s legacy feels urgent. And a crucial part of his work is that the beginning of his great known international works humbly occurred, in a little glamorous and sandy industrial building.

Discovering Soho

Christo, originally from Bulgaria, and Jeanne-Claude, originally from Morocco, with Paris in the 1950s. In 1964, they arrived in New York through the SS France. They brought with them two matees, a gerrit rietveld chair and a painting by Lucio Fontana. These articles do not easily fit into suitcases, but Christo “was a teacher in terms of wrapping and packaging,” Giovanelli said with a smile.

Like many artists of the time, the couple moved to the Chelsea hotel. They were looking for a more permanent place to stay, and the sculptor Claes Oldenburg, who is also live at the Chelsea hotel, suggested Christo and Jeanne-Claude, visit 48 Howard. Mr. Oldenburg had a study there and knew that several floors in the building were vacancies.

The building was owned by two brothers, Max and Ben Rosenbaum, who directed a tin roof business. They were charging $ 75 per floor in Rent-Christo and Jeanne-Claude decided immediately to move, taking the two upper floors.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude had to “literally build the walls, paint everything and scrub all filth,” Giovanelli said. They called other artist friends, including Gordon Matta-Clark, to help build a bathroom and cabinets. Then they had to provide the place.

With little money, the couple became “professional scavengers,” said Giovanelli. “He would literally like to walk the streets of Soho and Brooklyn and get furniture that other people ruled out.” While Christo was shy, Jeanne-Claude “was known for being shameless,” said Giovanelli. He would pretend not to know her while collecting chairs and street tables.

Objects at home “have a repeated patina,” said Yukie Ohta, an artist and archivist in Soho. “They are not quite dirty, but they are not as brilliant as the subzero or as fresh refrigerators as the room sofas and the board that one could find in a renewed loft soho today.”

In 1973, the Rosenbaums told Christo and Jeanne-Claude who planned to sell the building and that they had found a buyer. Jeanne-Claude asked if she and Christo could buy it instead if she could match the most symbolic offer $ 1. The owners said yes, but finance again were a problem for the couple.

“We try our best to get the money,” said Christo in a 2014 interview with T. “At that time, we sometimes hurry to pay the rent for a few months. But the owner, Mr. Rosenbaum, cools a mortar so we can buy the building.”

They ended up buying the building for $ 175,000.

Successful dinners

At first, only Christo was recognized as the artist behind the pieces, but in the mid-90s, he began to share the same credit for outdoor works with Jeanne-Claude. She also acted as her publicist and organizing dinners, influential invitations and gallery owners. “She was known for being a terrible cook,” Giovanelli said. “They had no money at all, so she would cook the steak and canned potatoes. That was all.”

The afternoons were often the source of gossip in the art world, Giovanelli added. They did not always select the list of guests carefully, and some of the attendees did not get along.

In the biography of Burt Chernow’s couple, the Ivan Karp dealership described one of the meetings as “a disastrous and gloomy night with some of the worst food served in a private house, never!”

Even so, some people returned: two frequent guests at dinner were Marcel Duchamp and his wife, Teeny.

In 1981, Willy Brandt, who had served as Western German Chancellor from 1969 to 1974, visited the house to discuss a apparently impossible project. Christo had a plot of legs to cover the Reichstag in fabric. The building has a dark history: in 1933, four weeks after Adolf Hitler became a chancellor, he caught fire. A fundamental moment in the rise of the Nazi regime, the event would be used to rationalize the massive judgment and the suspension of press freedom.

The German authorities repeatedly denied Christo and Jeanne-Claude permission to wrap the building. But they had the support of Mr. Brandt, who had reached 48 Howard to urge them not to surrender. In 1992, however, Mr. Brandt died. The couple continued to push.

The project became the issue of a vote in the German Parliament in 1994, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude won by 69 votes.

The following year, in his return from La Victoria, Christo declared his mission clearly. “No one can buy this project. No one can possess this project. No one can sell tickets for this project,” the Los Angeles Times told the week before his presentation. “Will this work exist?

Then, more than 200 workers covered silver cloth on the Reichstag. From the conceptualization to the realization, the project covered three decades; He remained wrapped for only two weeks. The exhibition cost more than $ 15 million, money that the couple won selling Christo’s sketches and models.

It was “the only time in history that the creation of a work of art was decided by a debate and a call vote in a parliament,” said Jeanne-Claud to Sculpture magazine in 2003.

A ‘sacred’ space

Christo’s study is “the most sacred part of the house,” said Giovanelli.

Entering the interior is like entering the mind of the great artist. Each element is meticulously organized: a single marker used to create “the red edge” is labeled and attached to a desk, a yoohoo can is reused to maintain pen. Technical drawings and maps abound, a plan with measurements to wrap the Snoopy booth booth, hangs on the wall next to a photo of Jeanne-Claude.

Jeanne-Claude’s footprint is also over. Where the radiator used to be, he tracked the words “I love you” of dirt on the wall. In the living room, he also hit pieces of paper with appointments that he enjoyed around space, one of what he says: “Being (Descartes) / do is to be (Jp. Sartre) / do be (Sinatra).”

The public anger and the institutional battles that came with each work were part of the art itself. “For me, aesthetics is everything in the process: workers, politicians, negotiations, construction difficulty, treatment with hundreds of people,” Christo told The Times in 1972. “The whole process questioned the process. I. Thetic. This is. I. Discover.

And he thought there were many triumphs, L’Cr of Trifphe, wrapped in Paris and the islands surrounded by Florida, there were also several occasions when the years of struggle did not lead to success.

As of the 1990s, the couple wanted to suspend almost six miles of luminous fabric over the Arkansas river. In 2011, two years after the death of Jeanne-Claude, Christo received the necessary permits to give life to the project. But then, the environmentalists protested, a local opposition group called Rags on the Arkansas River formed and the students of the Environmental Law Clinic of the University of Denver filed a lawsuit to stop the project. But only in 2017, after President Trump swore for the first time, Christo announced that he wanted to get away from him, in an act of his own protest.

“The federal government is our owner. They have the land,” Christo told The Times after his decision. “I can’t do a project that benefits this owner.”

I thought that physical installation never came to Fruity, in a way, work still existed through the conversations it caused. And it is still proudly exhibited in the house today is a bumper sticker made by rags on the Arkansas river, which says: “I just say no to Christo.”

Even now, the dialogues inspired by the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, generated by 48 Howard, are doing.

“The aura of the possible, which is what attracted people to Soho in the first place,” Ohta said, “emanates from the bones of the building.”

]