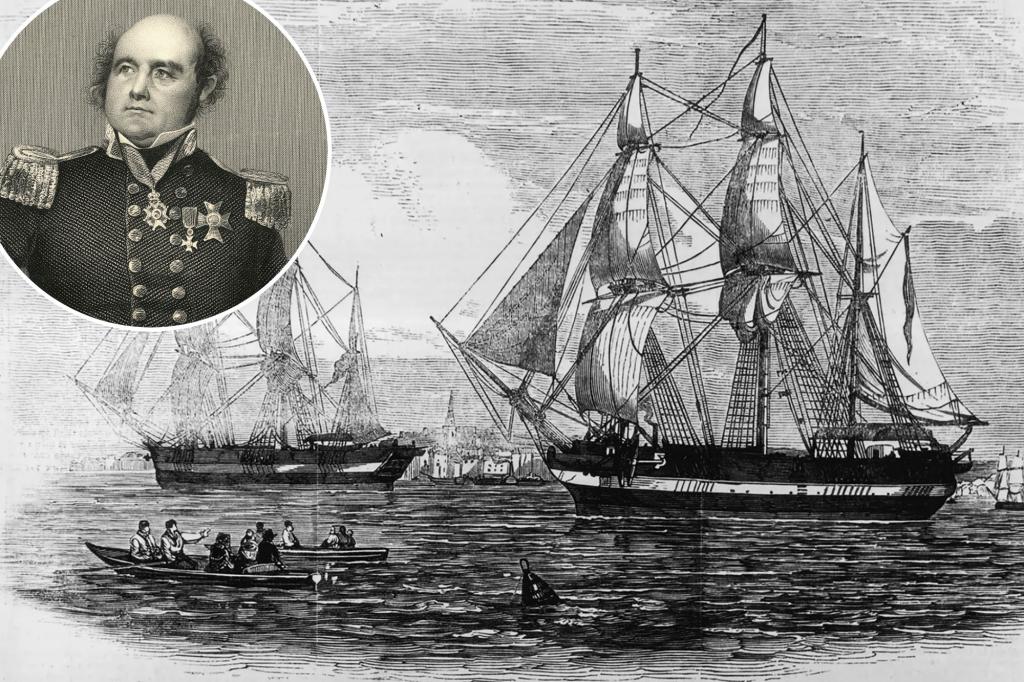

In May 1845, one of England’s most famous naval officers, Sir John Franklin, launched an expedition to discover the Northwest passage.

Once it was believed that it was ice free, the legendary journey of the north pole had the mythical leg described without any real evidence, such as earthly paradise with palm trees, dragons and 4 feet pigmers. Forget about snow storms, polar bears and Arctic typhoons.

But Franklin and a crew or 128 men never left the great northwest.

And what was known as “The Franklin Mystery” has led to more than 175 years of speculation and “generations generated from devote 175 years (Heton).

Synnott, a veteran of international expeditions of climbing, even in the Arctic, the Patagonia, the Himalayas, the Sahara and the Amazon Jungle, had made that what really happened to Franklin and its crew.

Therefore, he embarked on his 40 -year -old fiberglass boat, Polar Sun, from Maine through the Northwest passage to witness what Franklin found about two centuries before.

His greatest hope was to find the famous records and newspapers of the employer, possible on the island of King William in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where the two Franklin ships were stranded in 1846 and froze in the sea of lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies lies.

“Almost all the crushers in the registered history of the Franklin expedition have been lost due to the winds of time and have” morbid fascination “with what happened to the pattern that was stranded in the central Arctic.

Franklin’s grave and registration books are still out there. Finding them would be like finding the Holy Grail, writes the author. “In fact, I had climbed to Everest, and now here I was apparently going for the navigation equivalent.”

Synott never found Franklin’s frozen rest, but learned that he had died on June 11, 1847, two years after leaving England.

Moreoover, about 105 survivors of their crew crossed the ice and tundra, dragging their boats and waiting for open waters.

“But one by one, each sailor must have succumb to a variety or diseases that include, we can assume, hunger, tuberculosis, scurvy and trench foot,” writes Synnott while satting with its members with its open members looking at the open members.

It was here that Franklin’s crew probably abandoned his ships and went to a convicted march of death, ignorant of the dangerous polar bears that were traveling through the betrayal of ice workshops. They probably had a little more knowledge than the inuit people who had lived in the north for more than 4,000 miles, traveling with the seasons through dogs and kayaks, made the British chauvinistically believers who first discovered.

Inuit people knew how to eat “Greenland food: seafood, sea oils and whales and fatty meats that avoided scurvy when there were no fruits and vegetables.” In the same place, the members of the Franklin expedition hungry and were forced to eat other crew members.

In 1854, Dr. John Rae of the Hudson’s Bay company discovered that Franklin and his ships had been caught on ice since September 1846, and Franklin died almost a year later.

The explorers had left notes in tin containers who buried under rocks in King William Island, confirming that another 24 crew members died and the 105 remaining survivors left the ship and headed south towards the great fish river of Back.

Crossing the maritime lane with ice through the Arctic Ocean that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans had long been a dream with the explorers as a shortcut for the Far East, and for England, this Northern Route could break the strength of the colonial era of Spain.

When John Barrow, secretary of the British admiralty, made the offer in 1844 or 20,000 pounds sterling, the equivalent of $ 2.5 million today, for the discovery of “a passage from the north for vessels per sea between Leenen Tay, Franklin, Franklin, Franklin, Franklin, Franklin’s Franklin, years before the moment and retired for 18 years.

Franklin had legs to the Arctic three times and was a famous and deeply respected explorer nicknamed “the man who ate his boots” after half of his crew died in his first expedition and ate his own boat league to stay alive.

This time, the set turns with stores or 7,000 pounds or pipe tobacco, 3,600 gallons or rum of the western Indies proof of 135, 5,000 bear gallons and a daily food allocation for each sailor or three pounds or food.

Franklin Mania consumed the British public, and expeditions and search matches were only out to find mutilated corpses.

In the end, the author writes, “the Inuit held the keys of this kingdom.

]