China’s neighbors and U.S. allies worry that each side could misinterpret the other’s intentions. An underlying distrust has infected the relationship, former officials say.

A breakdown in communication between the United States and China is raising the risk of an unintended crisis or conflict between the two superpowers, current and former U.S. and Western officials say.

Diplomatic channels between China and the U.S. have mostly dried up as relations between the superpowers have steadily deteriorated over two successive administrations, with Beijing so far unwilling to say when top U.S. officials from the Biden administration will be welcome for high-level meetings.

Even if the two sides are able to arrange another phone call soon between President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping or a Cabinet-level meeting to discuss trade as White House officials hope, an underlying distrust has infected the relationship, according to former U.S. diplomats and Western officials.

“There’s just so much suspicion of intentions on each side,” said Susan Thornton, a former U.S. diplomat who worked in Asia. “The lack of communication just amplifies and escalates the downward spiral,” said Thornton, now a senior fellow at Yale Law School.

Although dialogue between China and the U.S. is at a standstill, Beijing is opening its doors to other governments, promoting itself as a global peacemaker ready to heal conflict in the Middle East and in Ukraine.

On Wednesday, Xi spoke to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the first time, saying Beijing “stands on the side of peace” and announcing plans to send an envoy “to have in-depth communication with all parties” in the war.

The phone call came after China rolled out the red carpet earlier this month for French President Emmanuel Macron and hosted the foreign ministers of Iran and Saudi Arabia, following a Chinese-brokered deal restoring diplomatic relations between the two regional rivals.

China’s neighbors and U.S. allies worry the breakdown in communication between the world’s superpowers could derail the global economy or lead to an accidental clash, with each side misinterpreting the other’s intentions, according to Western officials and former U.S. diplomats.

But China sees little value in pursuing talks with the Biden administration on trade or other issues, having concluded that the U.S. is seeking to block its economic progress and “encircle” its military, former officials and experts say.

“The regime has decided that we’re out to get them, and that we will not tolerate China’s rise to a point at which it could be a peer competitor, let alone displace us as king of the mountain,” said Thomas Fingar, a fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University who served in senior roles at the State Department.

Bonnie Glaser, managing director of the Indo-Pacific program at the German Marshall Fund, said it was unclear if and when China would agree to face-to-face talks with Biden’s top diplomat, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, or the treasury and commerce secretaries.

“They don’t see much to be gained from dealing with the United States. They’re not convinced that the U.S. agenda is advantageous to China,” Glaser said.

Instead, China is pursuing an ambitious global campaign as a power broker and trade partner, calculating that it can bolster its relations with an array of countries, particularly those outside of Europe and North America, without having to cultivate relations with the United States.

“China wants to show the rest of the world that it’s interested in peace, and in everything China does, it draws a contrast with the United States, saying, ‘We’re constructive, we’re promoting peace, while the United States is pouring oil on the fire by providing weapons to Ukraine,’” Glaser said.

The hawkish domestic political climate in both countries is helping to fuel the lack of dialogue, former officials say, as neither government wants to be seen to be weak or too willing to engage in talks.

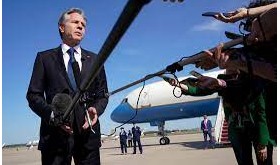

A planned visit by Blinken in February was supposed to thaw the ice and defuse some of the tension with Beijing. But a 200-foot-tall Chinese airship, which U.S. officials said was a spy balloon designed for eavesdropping, traversed the U.S. for several days before it was shot down by a U.S. fighter jet, prompting Blinken to cancel his trip. Some lawmakers sharply criticized the administration for not downing the balloon earlier.

Following the balloon episode, China and the U.S. have yet to agree on a rescheduled visit for Blinken.

The White House expects a phone call between Biden and Xi soon, a senior administration official said, and there are efforts to arrange meetings with the Chinese counterparts of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. Conversations between the two governments via embassies are continuing as usual, the administration official said.

But military-to-military talks have been suspended, despite repeated requests from Washington. And more than 100 communication channels between different government ministries and agencies are dormant, depriving each side of mechanisms that can defuse smaller disagreements and disputes.

Former intelligence officers and diplomats worry how the lack of communication could play out if there were an incident similar to a 2001 collision between a Chinese fighter jet and an EP-3E U.S. Navy surveillance aircraft near Hainan Island. That episode triggered a crisis, but relations between China and the U.S. were much better then.

In the current tense atmosphere, a mishap between the two militaries could quickly escalate with unpredictable consequences, said John Hamre, CEO of the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank.

“I think it would be really hard to control something if there was an EP-3-like incident now, because everybody is just primed to see dark motives and evil intentions,” said Hamre, who served as a senior Pentagon official in the 1990s.

Hamre signed on to an appeal last year from business executives and policy experts calling for restoring a constructive dialogue between the U.S. and China, arguing the two countries still had shared economic interests.

However, both the Biden administration and Xi’s government appear keen to avoid any sign that they are pleading for talks.

“The conventional wisdom in Washington now — as well as in Beijing — is having a dialogue just for dialogue’s sake is a waste of time, or a negative thing that shows weakness. So neither wants to do that,” said Kurt Tong, a former career U.S. diplomat and now managing partner at The Asia Group, a business advisory firm headquartered in Washington.

In years past, bilateral talks with China were candid and helped each side better grasp the other’s outlook, according to Michael Green, chief executive officer at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, who served in senior positions in George W. Bush’s administration.

But “things changed with Xi Jinping,” Green said.

The Chinese president’s iron grip on power curtailed what officials were prepared to say and Beijing adopted a view that the United States and its Western partners were in decline, Green said. U.S. rhetoric about an intense competition with China didn’t help either, he said.

“This combination of aggressive triumphalism over the West … plus his (Xi’s) opaque and authoritarian leadership style made it extremely difficult for the Biden administration to really get dialogue going,” Green said.

In a speech last week, Yellen offered what appeared to be a modest olive branch to Beijing, saying U.S. national security measures targeting Beijing were not meant to “stifle” the Chinese economy and that an attempt to decouple the U.S. from China’s economy would be “disastrous.”

The treasury secretary said the U.S. and China “can and need to find a way to live together” in spite of current strains.

In January, Yellen met her Chinese counterpart in Zurich, marking the highest-level contact between the two countries since Xi and Biden met in November.

China says the U.S. is to blame for tensions between the two governments.

“China and the U.S. maintain necessary communication,” said Liu Pengyu, spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington.

“The responsibility for the current difficulties in China-U.S. relations does not lie in China. The root cause is the misconceived China policy of the U.S. which is based on a misguided China perception.”

“The U.S. side should show sincerity, honor its words and take concrete actions to follow through on the common understandings” that were agreed between Xi and Biden in a meeting in Bali last year, the spokesperson said